Despite the official Roman gender ideology that relegated women to the private, domestic sphere, inscriptions, coins, and archaeological remains provide ample evidence that many wealthy Roman women played important public roles as priestesses and donors of major civic buildings in cities throughout the empire. Three women of differing backgrounds in two locations in the eastern empire provide significant examples of this phenomenon.

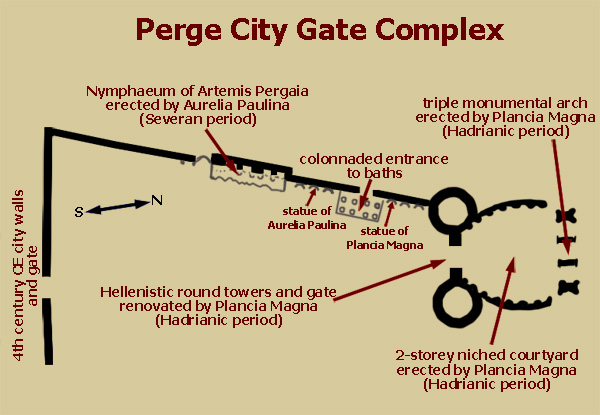

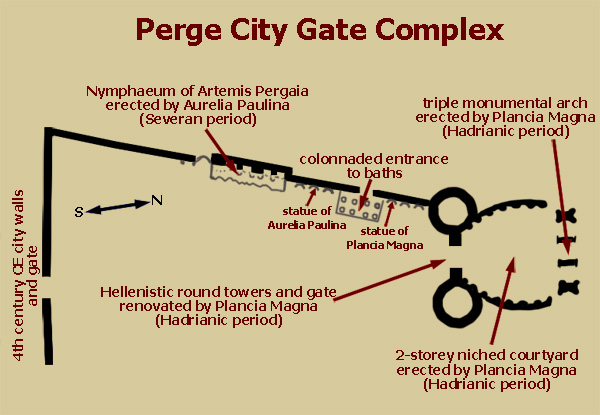

Perge was an important city in the Roman province of Pamphylia in Asia Minor (now southwest Turkey; see map). The monumental complex surrounding the southern gate of this city was adorned with magnificent structures donated to the city by two wealthy women, whose largesse was attested in numerous inscriptions and whose statues were prominently displayed in the complex. The schematic plan of the city gate complex below will give an idea of the location of these structures; clicking on the plan will show photos of the extant remains of these structures as they appear today. The effect of these concentrated female benefactions on ancient visitors to the city must have been very striking.

Plancia Magna: Plancia Magna was a Roman citizen, a member of the Plancii from Latium in central Italy who had emigrated to Perge sometime during the late Republic. The family had risen to prominence and great wealth over several generations to become members of the elite in Perge. Plancia's father, Marcus Plancius Varus, became a member of the Senate in Rome and rose to the position of praetor; he served as proconsular governor of the province of Bithynia (see

map) during the reign of Vespasian. Plancia's birth date is not known, but her major benefactions to the city were made during the reign of Hadrian (117-138 CE), and it is probable that a Plancius, either her brother Gaius Plancius Varus or her son, Gaius Julius Plancius Varus Cornutus, was consul in Rome and governor of Cilicia under Hadrian. Plancia's husband, Gaius Julius Cornutus Tertullus (only slightly younger than her father) had been suffect consul with Pliny the Younger in Rome in 100 CE, but her wealth apparently came from her paternal family; note the atypical insertion of her family name, Plancius Varus, in the name of her son.

Plancia Magna: Plancia Magna was a Roman citizen, a member of the Plancii from Latium in central Italy who had emigrated to Perge sometime during the late Republic. The family had risen to prominence and great wealth over several generations to become members of the elite in Perge. Plancia's father, Marcus Plancius Varus, became a member of the Senate in Rome and rose to the position of praetor; he served as proconsular governor of the province of Bithynia (see

map) during the reign of Vespasian. Plancia's birth date is not known, but her major benefactions to the city were made during the reign of Hadrian (117-138 CE), and it is probable that a Plancius, either her brother Gaius Plancius Varus or her son, Gaius Julius Plancius Varus Cornutus, was consul in Rome and governor of Cilicia under Hadrian. Plancia's husband, Gaius Julius Cornutus Tertullus (only slightly younger than her father) had been suffect consul with Pliny the Younger in Rome in 100 CE, but her wealth apparently came from her paternal family; note the atypical insertion of her family name, Plancius Varus, in the name of her son.

There were at least five statues and numerous inscriptions of Plancia Magna in Perge. These are mostly in Greek; see, for example, the inscribed base of her extant statue that stood on a niche in the wall outside the round towers of her gate (the other two niches also held statues of women, including another statue of Plancia Magna). These inscriptions closely link her with Perge, her native city; she is frequently termed “daughter of the city,” and she bears the title demiourgos (“one who works for the demos, the people”), which indicates that she was an annual eponymous magistrate whose name was used in dating (a very high honor for a woman). She was also the priestess of the chief deity of the city, Artemis Pergaia (Diana Pergensis in Latin) and “first and only priestess” of the Great Mother goddess; two inscriptions indicate that she was also a priestess of the imperial cult, and in the extant statue she wears a diadem adorned with small busts of emperors, symbol of that office (see this priest's crown with seven imperial busts and trailing ribbons, depicted on a bronze Cilician coin of Elagabalus).

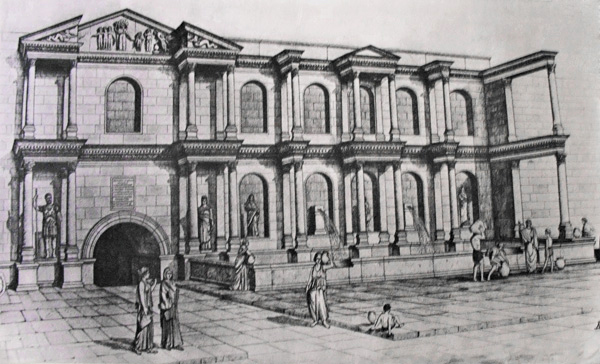

Sometime between the years 119 and 122 CE, Plancia Magna made her great donation to the city. She repaired and refurbished the large round towers of the main city gate, dating originally from the Hellenistic period. Immediately inside this gate she created an oval courtyard by adding two-storey curving walls, faced with marble and containing niches for statues (14 on each side); in front of these were two levels of Corinthian columns, giving the impression of a scaenae frons (the backdrop of the stage in a Roman theater). The lower niches all contained large statues of the gods, while smaller statues of legendary mythological figures stood in the upper niches along with a few historical men. Statue bases inscribed in Greek named Plancia Magna as donor and identified the statues; those in the upper register were each termed kistes (“city-founder”), and among these stood Marcus Plancius Varus and his son Gaius Plancius Varus, both strikingly called “father of Plancia Magna” and “brother of Plancia Manga.” Thus Plancia brought together Olympian deities, the mythological founders of her city, and members of her own family, who were identified with reference to her; it is interesting to note that her husband and son were apparently not represented in the courtyard. At the far end of this imposing courtyard stood a huge triple arch leading into the city; here were displayed statues of the Roman imperial family, including the deified Nerva, the deified Trajan, his surviving wife Plotina, Trajan's deified sister Marciana, Trajan's deified niece Matidia (mother of Sabina), the reigning emperor Hadrian, and his wife Sabina; there were also statues of Artemis Pergaia/Diana Pergensis and the guardian spirit (Tyche) of the city (for comparison, see this relief frieze from the theater at Perge, showing the goddess Tyche holding a carved tablet that symbolized Artemis Pergia). All the statue bases, inscribed in both Latin and Greek, named Plancia Magna as donor, and large bronze letters at the top of the arch proclaimed that Plancia Magna dedicated this arch to her city (unusually, since most such dedications were made to the emperor). On this monumental arch, female figures greatly outnumber males, and the well-preserved statue of the empress Sabina is executed in a traditional style that exactly parallels the extant statue of Plancia herself. Any visitor entering the city through this magnificant complex must have been greatly impressed by the way it united Perge with imperial Rome, bringing exceptional honor to Plancia Magna, to the Plancii family, and to the city and its traditions.

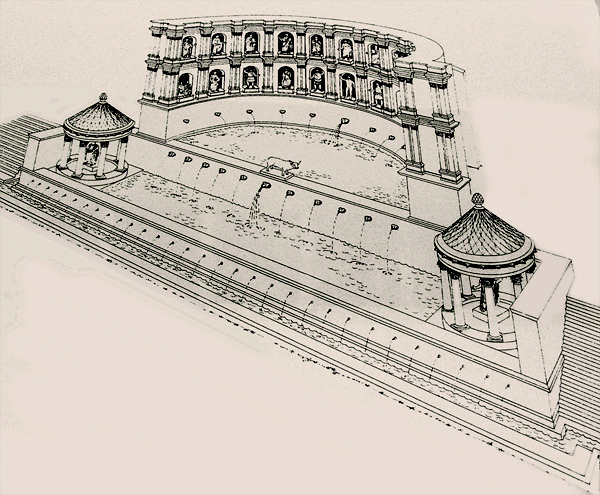

Aurelia Paulina: Unlike Plancia Magna, who preceded her by at least a generation, Paulina did not come from a senatorial Roman family. Born in the province of Syria, she had emigrated to Pamphylia, married a man named Aquilus from Sillyon, and received a grant of Roman citizenship from the emperor Commodus (180-192 CE), thus adding Aurelia to her name. She was obviously very wealthy, and inscriptions tell us that she held the offices of priestess of Artemis Pergaia and priestess of the imperial cult, a title she shared with her husband. Inspired by Plancia Magna's example, she located her great donation to the city in the trapezoidal courtyard outside the southern city gate, constructing a large monumental nymphaeum (fountain), shown in this reconstruction drawing above.

The extant remains of this nymphaeum do not reflect its magnificence. Like Plancia Magna's oval courtyard, it borrowed from the theatrical scaenae frons design, with a marble colonnaded facade and niches displaying statues. Inscriptions indicate that Aurelia Paulina constructed and decorated the fountain and that it was dedicated to Artemis Pergaia and the reigning emperor, Septimius Severus (193-211 CE), along with his wife Julia Domna and sons Caracalla and Geta (the latter's name was erased after he was killed by his brother in 211 CE). A lifesized statue stands between two other female statues just beyond the nymphaeum (see plan at top of page); the last statue of this trio may also represent Paulina, but only a fragment of the head survives. Unusually, the extant statue (shown at left) depicts Aurelia Paulina in Syrian dress; the heavy jewelry covering her chest is typical of Syrian female portraits from this period, and the long chain ending in a large shell pendant is associated with Artemis. She may have chosen this style of portraiture to emphasize a bond with the empress Julia Domna, who was also born in Syria. On the pediment over the large arch in the nymphaeum was a relief with distinctively feminine symbolism, depicting Eros, the three graces, Artemis Pergaia (damaged here but clearly shown in this column from Perge), a priestess, Dionysus, Aphrodite, and Eros. The priestess, with her large shell pendant, closely resembles the statue of Aurelia Paulina herself.

The nymphaeum was built over an ancient well in which was found a lovely statue of Artemis; it is thought that this statue may have stood in the niche immediately below the pediment. To the left of the large arch stood a statue of Septimius Severus, with a statue of Julia Domna on the right. The empress is shown with her right hand raised in prayer, forming another link with the priestess donor Paulina. Another statue from the fountain also depicted a Syrian, Julia Soaemias, niece of Julia Domna, or Julia Maesa, sister of the empress. The remaining niches most probably held statues of other members of the imperial family. Thus Aurelia Paulina has emulated her eminent predecessor in the priesthood of Artemis Pergaia, Plancia Magna, and brought honor to her adopted city of Perge and her native homeland of Syria along with the ruling dynasty in Rome. Moreover, residents and travelers alike must have blessed the name of Aurelia Paulina for the provision of easily accessible fresh water in this hot and dry area.

Olympia was a major Greek sanctuary in the Peloponnesian penisula of Greece (see map), home of the Olympian games held every four years from the eighth century BCE to the fourth century CE. It contained the most important ancient Greek temple of Zeus (whose famous cult statue is shown in this modern model), as well as other temples and structures associated with the games. This model illustrates part of the site during the Roman period; the white structure with high curved walls is the nymphaeum of Regilla:

Regilla: The length of Regilla's full name—Appia Annia Regilla Atilia Caucidia Tertulla—is an indication of the extremely high status of her aristocratic Roman family; through her father, Regilla was related to two empresses, Faustina the Elder and Younger. Born in Rome about 125 CE (shortly after Plancia Magna's donations to Perge and a generation before Aurelia Paulina), Regilla was married in 139 CE to Herodes Atticus, a wealthy and well-connected Greek rhetorician and Sophist living in Rome; the bride was about 14, while the groom was 40. Herodes had been the tutor of the emperor Antoninus Pius's adopted son Marcus Aurelius, who was married to the emperor's daughter Faustina the Younger and who became emperor in 161 CE; Herodes remained in this emperor's favor until his own death in 177 CE. Regilla bore five children, but only three survived to adulthood, two daughters and a son.

Regilla: The length of Regilla's full name—Appia Annia Regilla Atilia Caucidia Tertulla—is an indication of the extremely high status of her aristocratic Roman family; through her father, Regilla was related to two empresses, Faustina the Elder and Younger. Born in Rome about 125 CE (shortly after Plancia Magna's donations to Perge and a generation before Aurelia Paulina), Regilla was married in 139 CE to Herodes Atticus, a wealthy and well-connected Greek rhetorician and Sophist living in Rome; the bride was about 14, while the groom was 40. Herodes had been the tutor of the emperor Antoninus Pius's adopted son Marcus Aurelius, who was married to the emperor's daughter Faustina the Younger and who became emperor in 161 CE; Herodes remained in this emperor's favor until his own death in 177 CE. Regilla bore five children, but only three survived to adulthood, two daughters and a son.

Herodes moved his family to Greece a few years after the marriage, and Regilla spent the rest of her life in his lavish estates around Greece. Although cut off from her own influential family and friends in Rome, she must have been a part of the highest circle of society in Athens. She was awarded a newly created office in Athens as priestess of the goddess Tyche (Fortuna in Latin) and the venerable and long-established office of priestess of Demeter Chamyne in Olympia in 153 CE. This priestess was the only woman officially present at the Olympic games; she sat on or near the altar of Demeter Chamyne on the north side of the stadium in Olympia opposite the judges' stand (see plan) to view the competitions, so the priesthood was both a great honor and physically quite demanding.

As priestess of Demeter, Regilla used her own considerable wealth to erect a great nymphaeum (monumental fountain) at Olympia. Her husband, Herodes Atticus constructed an aqueduct that fed the nymphaeum, but it was Regilla's fountain that made the cool, refreshing water available to the people in this hot, dusty area (see the reconstruction drawing below or a Quicktime VR view of the extant remains). The fact of her donation is strongly stated in an inscription carved on the lifesized statue of a bull that stood in the center of nymphaeum: “Regilla, priestess of Demeter, dedicated the water and the things around the water to Zeus.” Bulls were sacrificed to Zeus, the chief divinity at Olympia, and the bull statue linked Demeter's cult to his; Zeus had assumed the form of a bull to carry off Europa, which Pausanias says was a surname for Demeter. The location of the nymphaeum also emphasizes the feminine, since it was situated between the temples of two great goddesses, Hera, goddess of marriage, and the Great Mother goddess (see plan).

Like Plancia Magna's courtyard and Aurelia Paulina's nymphaeum, Regilla's fountain borrowed the theatrical scaene frons design, with two levels of niches bearing statues and a columnar facade. Enough statue bases and statues (many of them headless) survive to enable scholars to make a plausible reconstruction of the way the 22 niches were filled. The central niche on each level held a statue of Zeus, surrounded by identified portrait statues on each side. The lower register contained statues of the reigning emperor, Antoninus Pius, and his ancestors and descendants, including the previous emperor, Hadrian; his wife, Faustina the Elder; his daughter Faustina; his adopted son, the future emperor Marcus Aurelius; and several of Aurelius's children, such as his daughter Annia Faustina (about 7 at the time but shown as a young adolescent). On the upper level, paralleling the imperial family, were statues of Regilla and Herodes and their ancestors and children, including Regilla's father, mother, and maternal grandfather; Herodes' father and mother; and their four children who were alive at the time, including their second daughter Athenais (about 10 at the time but also shown as an adolescent). Regilla's statue, above right, is unfortunately now headless, but she is depicted in the traditional garments and pose that we have already seen used for Plancia Magna, suitable for respectable Greek and Roman women, elite matrons and empresses alike. Because of its height and gleaming marble, the nymphaeum stood out among the surrounding buildings, bringing great honor to both the women and the men of Regilla's family and emphasizing their links with the imperial family in Rome.

It is not possible to know for certain how Regilla's contemporaries viewed her in relation to this magnificent donation to Olympia, but most modern scholars effectively erase her from this monument by terming it “the nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus,” despite the emphatic inscription on the bull. Unlike Plancia Magna or Aurelia Paulina, Regilla was married to a man who was famous (and infamous) in his own time and very well-attested in literature and inscriptions that have survived to the present day. Indeed, Regilla may have lost her life as well as her fame to this man, since she died in 160 CE, 35 years old and eight months pregnant, from being kicked in the abdomen by a freedman of Herodes named Alcimedon. Regilla's brother Bradua brought charges in Rome against Herodes, alleging that he had been responsible for the death, but Marcus Aurelius was by this time emperor and exonerated his old tutor. Regilla's story is brilliantly told in Sarah Pomeroy's book The Murder of Regilla: A Case of Domestic Violence in Antiquity; Pomeroy builds a convincing case for the ultimate guilt of Herodes.

Photos of the Aurelia Paulina statue, Artemis column relief, and nymphaeum pediment relief are used with the kind permission of Linda Davis.