|

|

| Macurdy siblings with birth dates standing: Grace (1866), William (1864); seated, middle: Edith (1862), Theodosia (1858), Maria (1860); seated, front: John (1873), Leigh (1876) |

|

|

| Macurdy siblings with birth dates standing: Grace (1866), William (1864); seated, middle: Edith (1862), Theodosia (1858), Maria (1860); seated, front: John (1873), Leigh (1876) |

“My mother had a large family, nine of us, and high ideals of education for her means. I educated the two youngest brothers as a sort of sacred task, because my mother felt that her children must have college training, if possible. So I gave up all sorts of things for them, as we all did.” (letter of Grace Macurdy to Gilbert Murray, 4 February 1911)

The Early Years: When Simon Angus McCurdy, the carpenter grandson of a loyalist Scotch-Irish immigrant from Rathlin Island, married Rebecca Manning Thomson, a minister's daughter, in St. Andrew's, New Brunswick, they began producing children in rapid succession. Their first child, Eliza, was born in 1856 but died at the age of four. After the birth of two more daughters and a son, Simon and Rebecca moved across the St. Croix River to the tiny town of Robbinston, Maine (listed as having 150 inhabitants in an 1895 atlas), where Grace Harriet, called Hattie by the family, was born on September 12, 1866. By the following December, Simon and his brother Warren had already left Maine to seek work in Massachusetts, leaving Rebecca alone to care for his elderly parents plus five lively children; in a letter to her brother-in-law written in 1867, she writes, “They are beautiful children and quite as noisy as I would wish for. I can scarcely hear my own ears.” Rebecca must have been quite relieved when the whole family moved to Watertown, Massachusetts, in 1870. Sometime in this period the spelling of their name was changed to Macurdy. As Grace later explained to her nephew Ernest, “Uncle Warren . . . was so afraid of being taken for Irish that he changed the spelling of our name. . . . It was very foolish of him and he made my poor father follow him.”

Three more sons were born in Watertown, but the last, Ronald, did not survive the year of his birth (1879). According to the census, all the Macurdy children were living at home in 1880, with most still listed as “at school,” though Maria was “teaching school.” William had graduated with honors from Watertown High School in an accelerated three-year program and was already working in the dry goods store which he would eventually own. Finances were obviously tight, but in 1884, apparently with the full support of her mother, Grace applied for admission to the recently opened “Harvard Annex” (officially called the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women). She successfully passed the Harvard Examinations for Women. Essentially the same as the admissions examinations for men, these included eleven subjects—Latin (Caesar and Vergil), Latin sight translation, Greek (Xenophon and Homer), Greek sight translation, ancient history and geography, arithmetic, algebra, plane geometry, physics, English composition, and French or German.

In the fall of 1884, Grace began commuting to “the Annex on Appian Way” in Cambridge as one of a small number of young women pursuing the regular four-year course of instruction. She later described this period as “a time of strenuous study and work,” and her talent and dedication earned her A's and A+'s on all her Greek and Latin courses, some of which were taught by the famous Harvard classicists William W. Goodwin and James B. Greenough. She earned her B.A. Certificate in 1888; this was retroactively changed to a Radcliffe degree upon the charter of Radcliffe College in 1894. From 1888-1893, Grace taught Latin and Greek at the Cambridge School for Girls and continued to take post-graduate courses at the Annex. Grace's salary helped to send her brother John to Harvard in preparation for his career as a civil engineer. After her mother died in 1895, Grace made sure that funds were available to send her youngest brother, Leigh, to Harvard and on to Boston University for a law degree.

“I have already written to Mrs. Hallowell that ‘you were one of our favorite pupils at Radcliffe and an excellent specimen of the finished product, a lady of fine strong character, excellent abilities and superior attainments.’ And further that ‘I could hardly imagine a better place of educational investment being sure that you would well repay any such outlay.’ I am so confident of the truth of all this that I am willing to say it to your face.” (letter of Professor James B. Greenough to Grace Macurdy, 19 January 1899)

Vassar College: In 1893, Grace Macurdy was hired to teach in Vassar's Greek Department. Abby Leach, who headed the department, was popularly credited with being the catalyst for the founding of the Harvard Annex, since the success of her own arrangement for private tuition in Greek and Latin from Professors Goodwin and Greenough had convinced them of the viability of teaching women. She was the first woman to serve as president of the American Philological Association (1899-1900) and was also president of the Association of Collegiate Alumnae (later called the AAUW) from 1899-1901. Leach initially encouraged Macurdy to pursue graduate studies at Columbia University while she taught at Vassar, and Grace won a fellowship from the Boston Women's Educational Association which enabled her to study at the University of Berlin with the famous classical scholar Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff from 1899-1900. By 1903, Macurdy had completed her dissertation on “The Chronology of the Extant Plays of Euripides,” received the Ph.D. from Columbia, and been promoted to Associate Professor. In 1908, Columbia University hired her to teach Greek in their summer program, which she did for the next eleven years; known as “the lady professor,” she was the first woman to teach in Columbia's academic program. Most of her students were men, frequently college graduates who wished to begin or continue their study of Greek.

By 1907, however, Abby Leach was assiduously campaigning to have Macurdy removed from the faculty. Arguing that a small department like Greek did not need an associate professor as well as a professor, Leach maintained that she could carry on perfectly well with only an assistant to help her. When these arguments proved unsuccessful, Leach turned to criticisms of Macurdy's scholarship, teaching, and even her trustworthiness. As head of the department, Leach began restricting Macurdy to the least popular and significant courses, changing her schedule unaccountably, and counselling students away from her elective courses. Macurdy fought back with appeals to the President for “a fair division of the work,” and President Taylor and the trustees repeatedly affirmed their respect for Macurdy as both teacher and scholar. Even after Macurdy's position was renewed in 1910 (though without a specified term), Leach did not give up her campaign, causing a minor academic scandal known outside the walls of Vassar. The papers documenting this conflict fill an entire box in the James Monroe Taylor collection in Vassar's archives and provide a graphic reminder that the obstacles facing early woman scholars were not all erected by men (a dramatic reading of this episode in Macurdy's life has been presented at a number of venues). The story did not really end until Leach's death in 1918.

“On the second day of my term there entered my office Miss Abbie [sic] Leach, Professor of Greek, bearing a satchel which she emptied upon my desk. ‘These documents,’ she said, ‘constitute the basis of my charges against Miss Macurdy, the other member of my department.’ . . . I stood up, gathered the papers solemnly, replaced them in Miss Leach’s bag, and placed it by her side. ‘Miss Leach, take back these papers, and never let me see or hear of them again. My administration began yesterday. It will never review what happened yesterday or the day before that.’. . . Not that the matter was ended. When I recommended Grace Macurdy for promotion, as I did at the end of the semester, it was without Miss Leach’s approval. In its place, I had a dozen letters from scholars of equal eminence in the faculty. Miss Macurdy won her way to eminence as a scholar, writer, and teacher, and today is remembered as one of the most distinguished professors in Vassar’s long list. . . . Let it be said at once that Miss Abbie Leach was also a distinguished woman and teacher of no common quality. . . .To her further credit be it recorded, that when she knew of her own mortal illness, she arranged to pay a formal call upon Miss Macurdy in her chambers, and drank the tea of reconciliation with her. It was a heroic act, worthy of Thermopylae.” (Henry Noble MacCracken, who took up the presidency of Vassar in 1915, in his book The Hickory Limb, 64-65)

|

| Grace with her great-nephew Jack Macurdy, 1912 |

The Productive Years: In 1916, Grace Macurdy received a permanent appointment as Professor of Greek at Vassar, but her new-found security was soon threatened by increasing deafness. Doctors were unable to stop her progressive hearing loss (despite measures like prescribing a “raw fruit diet”), and Grace learned to cope with the various hearing aids available at the time, including ear trumpets and large black boxes with microphone devices. She must have also learned to lip read, since she functioned much better in one-on-one conversations, and she was so popular with the students that they conspired to protect her from some of the consequences of her deafness in class. In any case, it is clear that Macurdy did not let her deafness prevent her from doing anything, since the last thirty years of her life were filled with international travel, research, writing, and world-wide friendships.

Macurdy was elected to a three-year term on the Executive Committee of the American Philological Association in 1915 (“which we women hailed as a recognition of us as the Philological Association has been so conservative about us”). She was appointed to the chairmanship of the Greek department in 1919, a position she held until her retirement in 1937, and also served on the Managing Committee of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens from 1919 to 1937. Although she had previously made several brief trips to England and the continent, her first sabbatical in 1922-23 enabled her to travel through northern Greece and the Balkans and spend considerable time conducting research in the library of the British Museum. She subsequently spent most summers abroad, as well as a half year in 1930 and a full year in 1937-38, and her interest in Hellenistic history led her to follow Alexander the Great into Egypt and western Asia.

“I must say the atmosphere of classical study in America is far from stimulating. Really I think the most living person I met there was Miss Macurdy of Vassar. She may be a little mad about the Paeonian Apollo, but it is the right sort of madness.” (letter of J. A. K. Thomson to Gilbert Murray, 26 August 1921)

Outside of Vassar and her extended family, Macurdy's closest friends were all British classicists. She had met Gertrude Mary Hirst, a graduate of Newnham College in Cambridge University, when both were completing graduate degrees at Columbia. Hirst was hired to teach at Barnard College in 1901, and she and Macurdy became lifelong friends, visiting each other frequently. Macurdy's friendship with the famous Oxford classicist and man of letters Gilbert Murray began when she sent him the printed version of her dissertation. They met when Murray lectured at Vassar in 1907, and they conducted a warm correspondence until Grace's death in 1946. She occasionally visited the Murrays in Oxford. Though she and Murray were exactly the same age, there was always a touch of hero-worship in her attitude toward him, but her friendship with James Alexander Kerr Thomson, Professor of Classical Literature at King's College London from 1923 to 1945, was much more of a peer relationship, despite the fact that he was thirteen years younger. Thomson and Macurdy met when he was a visiting lecturer at Harvard, and they became close friends during the year he taught at Bryn Mawr as a leave replacement (1921-22). During her sabbatical the following year, Macurdy worked closely with Gilbert Murray to help secure a more permanent position for Thomson either in Britain or America, and their efforts finally bore fruit in the post at King’s College. Thereafter Macurdy saw Thomson frequently; her addresses in London were always close to his and they frequently travelled together in Europe. They also amassed a joint collection of classical artefacts; after Macurdy's death, half of the collection was given to Vassar’s Classical Museum and the other half to Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum.

Family History: Grace Macurdy, like many other professional women of her era, never married, but throughout her life she maintained very close ties with her extended family. She jointly owned a summer house in North Falmouth, Massachusetts, with her sister Theodosia, a librarian in the Boston Public Library and the only other Macurdy sibling to remain single. Family legend has it that the house was built by a carpenter whose marriage proposal to Grace had been kindly but firmly refused. She kept in close touch with her eight nieces and nephews; in fact, her niece Theodosia Skinner and nephews Richard and Bradford Skinner lived with her for a time at Vassar after their mother, her widowed sister Edith, died in 1918.

“We have extraordinarily interesting and colorful ancestors. . . . We have all been brought up in great ignorance of our ancestors & the part they played in the early history and making of America.” (letters of Grace Macurdy to her nephew Ernest Macurdy, 15 September 1934 and 10 September 1945)

|

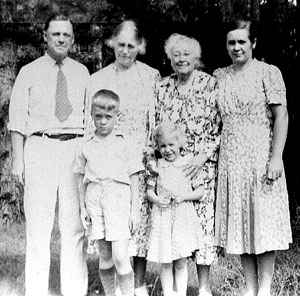

| Grace with her niece Theodosia (daughter of Edith), flanked by her nephew Ernest (son of William), his wife Helen, and their children William Bradford Macurdy and June Harriet Macurdy, 1941 |

One of Macurdy's last writing projects was to compile the family genealogy. At the behest of her cousin Horace W. McCurdy, a shipbuilder whose Puget Sound & Dry Dock Company was the second largest employer in Seattle in 1939, Grace undertook the arduous task of documenting the McCurdy family roots. In 1944 she sent to Horace a manuscript entitled “Pioneer Ancestors of an American Family, 1620-1857.” Much of the information she uncovered was published in 1963 as part of a book privately printed by Horace McCurdy, Genealogical History of James Winslow McCurdy and Neil Barclay McCurdy. Though her eyesight was steadily failing due to cataracts, Grace expanded her genealogical research to her mother’s side of the family, discovering to her delight that she and her siblings could claim descent from eight of the twenty-two Mayflower passengers who left offspring, including Governor William Bradford.

During her last years, Macurdy was plagued by financial worries, particularly how she was going to pay for an expensive cataract operation so she could read and write again. She eventually raised the money by selling her summer house to her nephew Ernest. The operation was successful, but on October 23, 1946, she succumbed to breast cancer.

Barbara F. McManus, <bmcmanus@cnr.edu>