| ROMAN CLOTHING |

|

| citizen, matron, curule magistrate, emperor, general, workman, slave |

| ROMAN CLOTHING |

|

| citizen, matron, curule magistrate, emperor, general, workman, slave |

“Dress for a Roman often, if not primarily, signified rank, status, office, or authority. . . . The dress worn by the participants in an official scene had legal connotations. . . . The hierarchic, symbolic use of dress as a uniform or costume is part of Rome's legacy to Western civilization.” (Larissa Bonfante. "Introduction.” The World of Roman Costume. Ed. Judith Lynn Sebesta and Larissa Bonfante. University of Wisconsin Press, 1994. Pp. 5-6)

I. Clothing and Status: Ancient Rome was very much a “face-to-face” society (actually more of an “in-your-face” society), and public display and recognition of status were an essential part of having status. Much of Roman clothing was designed to reveal the social status of its wearer, particularly for freeborn men. In typical Roman fashion, the more distinguished the wearer, the more his dress was distinctively marked, while the dress of the lowest classes was often not marked at all. In the above diagram, for example, we can deduce that the first man on the left is a Roman citizen (because he wears a toga) but is not an equestrian or senator (because he has no stripes on his tunic). We know that the woman is married because she wears a stola. Colored shoes and the broad stripes on his tunic identify the next man as a senator, while the border on his toga indicates that he has held at least one curule office. The laurel wreath on the head of the next man and his special robes indicate that he is an emperor, while the uniform and cloak of the following man identify him as a general. It is more difficult to determine the exact social status of the two men on the right; their hitched-up tunics indicate that they are lower-class working men, but the two lowest social classes in Rome (freedpeople and slaves) did not have distinctive clothing that clearly indicated their status. These men could both be freedpeople (or citizens at work, for that matter); however, the man in the brown tunic is carrying tools and the other man is lighting his way, so we can deduce that the man in the white tunic may be a slave of the other man.

Augustus and later emperors emphasized the interaction of dress, social status, and public display when they required official dress at public performances and regulated public seating in the theaters and amphitheaters of Rome. A prominent section was reserved for the male and female members of the imperial family and the 6 Vestal Virgins; the first rows were reserved for senators, the next for male equestrians, the next for male citizens (with women of all classes relegated to the top rows of this section), and the top "standing room only" tiers for the lowest classes. Performers and spectators at these events would thus see a striking visual display of the different status groups in the form of blocks of color created by the different types of togas (the modern film Gladiator recreated this effect in the computer-assisted simulation of the Colosseum).

II. Production and Cleaning of Garments: Typically, Roman garments were made of wool. In the early Republic, women spun the fleece into thread and wove the cloth in the home, and doubtless many women of the less wealthy classes continued this practice throughout the history of Rome. By the late Republic, however, upper-class Roman women did not spin and weave themselves (unless, like Livia, they were trying to demonstrate how traditional and upright they were). Instead, slaves did the work within the household or cloth was purchased commercially, and well-to-do Romans could also buy cloth made of linen, cotton, or silk. There were many businesses associated with textiles besides spinning and weaving, including operations such as dyeing (fibers were usually dyed before being spun into thread), processing, and cleaning. Garments were cleaned by fullers (fullones) using chemicals such as sulfur and especially human urine.

III. Undergarments: We do not know a great deal about Roman underclothes, but there is evidence that both men and women wore a simple, wrapped loincloth (subligar or subligaculum, meaning “little binding underneath”) at least some of the time; male laborers wore the subligar when working, but upper-class men may have worn it only when exercising. Women also sometimes wore a band of cloth or leather to support the breasts (strophium or mamillare). Both these undergarments can be seen on the woman athlete at the left, from a fourth-century CE mosaic; she holds a palm branch signifying that she has been victorious in a contest. (see another scene from this mosaic and an ancient pair of leather “bikini” pants found in Roman Britain.)

IV. Footwear: Sandals (soleae, sandalia) with open toes were the proper footwear for wearing indoors. There were many different designs, from the practical (as shown in this model or this foot of a statue) to elegant (as shown in this actual leather woman's thong-style sandal with a gold ornament). Shoes (calcei), which encased the foot and covered the toes, were considered appropriate for outdoors and were always worn with the toga; when visiting, upper-class Romans removed their shoes at the door and slipped on the sandals that had been carried by their slaves. There were many different styles of shoes, and some leather versions have survived, like these shoes (ancient leather shoes on top and modern reconstructions below) and this simple workman's shoe. There were no dramatic gender differences in Roman footwear (unlike the high heels worn by women today), though upper-class males (equestrians, patricians, and senators) wore distinctive shoes that marked their status; the patrician shoes, for example, were red.

V. Men's Clothing:

| THE TUNIC | ||

|

|

|

| basic tunic (tunica) |

equestrian tunic (tunica angusticlavia) |

senatorial tunic (tunica laticlavia) |

The basic item of male dress was the tunic, made of two pieces of undyed wool sewn together at the sides and shoulders and belted in such a way that the garment just covered the knees. Openings for the arms were left at the top of the garment, creating an effect of short sleeves when the tunic was belted; since tunics were usually not cut in a T-shape, this left extra material to drape under the arm, as can be clearly seen in this statue of a first-century CE orator in tunic and toga. Men of the equestrian class were entitled to wear a tunic with narrow stripes, in the color the Romans called purple but was more like a deep crimson, extending from shoulder to hem, while broad stripes distinguished the tunics of men of the senatorial class. Most ancient statues do not show these stripes, but this wall painting from a lararium in Pompeii depicts both the tunica laticlavia and toga praetexta. As can be seen in the drawing at the top of this page, working men and slaves wore the same type of tunic, usually made of a coarser, darker wool, and they frequently hitched the tunic higher over their belts for freer movement. Sometimes their tunics also left one shoulder uncovered, as depicted in this mosaic of a man named Frucius (whose narrow stripes indicate equestrian rank) being attended by two slaves, Myro and Victor. Slaves were not inevitably dressed in poor clothing, however; Junius, the young kitchen slave depicted in this mosaic, wears a more elegant tunic and a gold neckchain, and the skeleton of a woman was recently found in an area near Pompeii with a quantity of gold jewelry, including a serpent bracelet engraved DOM[I]NUS ANCILLAE SUAE, “from the master to his slave girl.”

| THE TOGA |

|

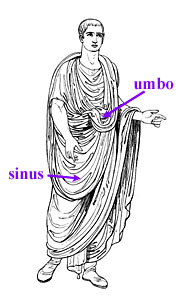

The toga was the national garment of Rome; in the Aeneid, Virgil has the god Jupiter characterize the Romans as “masters of the earth, the race that wears the toga” (1.282). Only male citizens were allowed to wear the toga. It was made of a large woolen cloth cut with both straight and rounded edges; it was not sewn or pinned but rather draped carefully over the body on top of the tunic. Over time, the size and manner of draping the toga became more elaborate; compare this bronze statue from the beginning of the first century BCE with this statue of a Roman senator or this statue of the emperor Augustus, which clearly illustrate the toga as worn during the late Republic and first centuries of the Empire. As shown in the drawing at left, the cloth was folded lengthwise and partly pleated at the fold, which was then draped over the left side of the body, over the left shoulder, under the right arm, and back up over the left arm and shoulder. It was held in place partly by the weight of the material and partly by keeping the left arm pressed against the body. The large overfold in the front of the body was called a sinus, and part of the material under this was pulled up and draped over the sinus to form the umbo. The back of the toga was pulled over the head for religious ceremonies, as in this statue of Augustus as chief priest (pontifex maximus). It was difficult to put the toga on properly by oneself, and prominent Romans had slaves who were specially trained to perform this function. Togas were costly, heavy, and cumbersome to wear; the wearer looked dignified and stately but would have found it difficult to do anything very active. Citizens were supposed to wear togas for all public occasions (here, for example, is a man being married in a toga), but by the beginning of the Empire Augustus had to require citizens to wear the toga in the Forum. This fresco from a building outside Pompeii is a rare painted depiction of Roman men wearing togae praetextae participating in a religious ceremony, probably the Compitalia; the dark crimson (Roman purple) color of their toga borders can clearly be seen.

The color of the toga was significant, marking differences in age and status:

Male children of the upper classes also had distinctive dress for formal occasions. All freeborn citizen boys were entitled to wear a bulla (see below). On formal occasions, boys also wore the toga praetexta, possibly over a striped tunic; in theory all freeborn citizen boys could wear this garment, but because of its expense it generally indicated that the wearer belonged to the upper class (see these boys on the Ara Pacis and this statue of the future emperor Nero wearing a bulla and an elaborately draped toga). At the age of 14-16, boys laid aside the bordered toga during their coming-of-age ceremony (usually celebrated on the feast of the Liberalia, March 17) and ceremonially donned the toga virilis.

Although women had apparently worn togas in the early years of Rome, by the middle of the Republican era the only women who wore togas were common prostitutes. Unlike men, therefore, women had an item of clothing that symbolized lack of (or loss of) respectability—the toga. While the toga was a mark of honor for a man, it was a mark of disgrace for a woman. Prostitutes of the lowest class, the street-walker variety, were compelled to wear a plain toga made of coarse wool to announce their profession, and there is some evidence that women convicted of adultery might have been forced to wear “the prostitute's toga” as a badge of shame.

|

Jewelry: Propriety demanded that adult male citizens wear only one item of jewelry, a personalized signet ring that was used to make an impression in sealing wax in order to authorize documents. Originally made of iron, these signet rings later came to be made of gold, like the ring at left, whose carnelian sealstone depicts a tragic actor holding a mask (see this large bronze signet ring from Herculaneum with the letters of the owner's name in reverse, for stamping on wax: M[arci] PILI PRIMIG[genii] GRANIANI.). The reverse lettering on this gold signet ring from the third century CE says CORINTHIA VIVAT, “may Corinthia live” or “long live Corinthia.” Other rings with a practical function were actually keys (see also this bronze ring with a more elaborate key), perhaps to the gentleman's strongbox. Literary evidence indicates that some Roman men ignored propriety and wore numerous rings as well as brooches to pin their Greek-style cloaks (like this silver pin with symbols of victory—a winged goddess with an eagle, laurel crown, and palm branch). Before the age of manhood, Roman boys wore a bulla, a neckchain and round pouch containing protective amulets (usually phallic symbols), and the bulla of an upper-class boy would be made of gold. See this terra-cotta statue of a baby wrapped in swaddling clothes and wearing a bulla, and this statue of a proud mother pointing to her son in his toga and bulla (the facial features and hairstyles indicate that this statue probably represents Agrippina the Younger and her son Nero). Boys sometimes wore small gold rings carved with a phallus for good luck |

Hairstyles:During the middle and late Republic and into the early Empire, Roman men wore their hair short and were clean shaven, even though the process of shaving was uncomfortable and frequently resulted in cuts and scratches. Emperors, however, became style setters. The emperor Nero (54-68 CE) affected a more elaborate hairstyle with curls framing his face and later added sideburns, which can also be seen on his coins. Hadrian (117-138 CE) was the first emperor to adopt a short beard, and many men, no doubt grateful to escape the ordeal of shaving, followed his example. After his reign, in fact, beards became quite common among Roman men.

Continue with Roman Clothing, Part II for information on women's clothing, hairstyles, and jewelry.

Barbara F. McManus, The

College of New Rochelle

bmcmanus@cnr.edu

revised August,

2003