|

THE CIRCUS: |

The first-century CE satirist Juvenal wrote, “Long ago the people shed their anxieties, ever since we do not sell our votes to anyone. For the people—who once conferred imperium, symbols of office, legions, everything—now hold themselves in check and anxiously desire only two things, the grain dole and chariot races in the Circus” (Satires 10.77-81). Juvenal's famous phrase, panem et circenses (“bread and circuses”) has become proverbial to describe those who give away significant rights in exchange for material pleasures. Juvenal has put his finger on two of the most important aspects of Roman chariot races—their immense popularity and the pleasure they gave the Roman people, and the political role they played during the empire in diverting energies that might otherwise have gone into rioting and other forms of popular unrest. The image above bears witness to the popularity of the races; found in the imperial baths in Trier (Germany), this centerpiece of a large mosaic floor depicts a charioteer for the Reds, holding in his hands the palm branch and laurel wreath, symbols of victory. Both the driver, Polydus, and his lead horse, Compressor, are identified by name, as though they were great state heroes. We can deduce something of the political role of chariot racing from the fact that the same word, factiones, was used to designate the four racing stables as had been applied to the political factions (the populares and the optimates) that had such large followings in the Republic.

Origins: Possibly the oldest spectacular sport in Rome, chariot racing dates back at least to the sixth century BCE. It was quite popular among the Etruscans, an advanced civilization of non-Italic people who for a time dominated the area around Rome and contributed greatly to many aspects of Roman civilization. We can also see depictions of chariot racing among the Lucanians of Sicily in the fifth century BCE. Among these peoples, races were associated with funeral games, and in Rome too they had religious ties, particularly to the chariot-driving deities Sol (the sun) and Luna (the moon), and to a god called Consus, an agricultural deity who presided over granaries. Originally chariot races (ludi circenses) were held only on religious festivals like the Consualia, but later they would also be held on non-feast days when sponsored by magistrates and other Roman dignitaries.

| CIRCUS MAXIMUS |

|

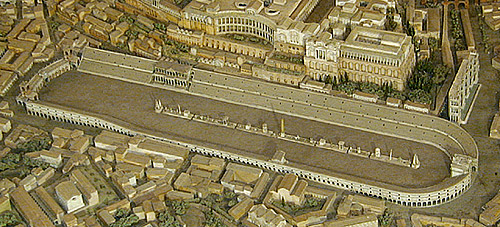

Races were held in a circus, so named because of its oval shape. The oldest and largest circus in Rome was the Circus Maximus, built in a long valley stretching between two hills, the Aventine (bottom left in this model shown ) and the Palatine (top right). Originally there was no building, just a flat sandy track with temporary markers; spectators sat on the hill slopes on either side of the track. Gradually the area developed into a well-maintained stadium-style building with a central divider, starting gates at one end (top left in this picture) and an arch at the other, surrounded on three sides by stands (originally wooden but later made of stone). By the time of Augustus, the entire building was 620 meters long (678 yards) and about 140-150 meters (159 yards) at its widest point; its seating capacity was approximately 150,000 spectators. This is a plan of the Circus Maximus, and this reconstruction drawing of the circus from the starting gate end shows the construction of the stands. This terracotta lamp depicts a chariot race in the Circus Maximus; on the left one can see rows of spectators, on the right the starting gates, and at the bottom the spina with its statues and obelisks. The form of the circus closely followed its function; for further details about the various structures in the circus and how they related to the races, see starting gates, track, barrier, turning posts, finish line, stands, and imperial enclosure.

Enjoy a virtual day at the races by visiting the Circus Maximus in Region XI of VRoma, either via the web gateway or the anonymous browser.

Charioteers and Racing Factions: Chariot racing was the most popular sport in Rome, appealing to all social classes from slaves to the emperor himself. This appeal was no doubt enhanced by the private betting that went on, although there was no public gambling on the races. The popularity of chariot racing is reflected in the many household items decorated with racing motifs, like these two terra-cotta lamps depicting victorious chariots in procession, this this signet ring with a circus scene, and this fragment of a glass bowl, and this child's toy. This fanciful mosaic shows a little boy dressed like a charioteer and receiving a palm of victory, even though his steeds are birds!

Although most Roman charioteers (called aurigae or agitatores) began their careers as slaves, those who were successful soon accumulated enough money to buy their freedom. The four Roman racing companies or stables (factiones) were known by the racing colors worn by their charioteers; this mosaic depicts a charioteer and horse from each of the stables, Red, White, Blue, and Green. Fans became fervently attached to one of the factions, proclaiming themselves “partisans of the Blue” in the same way as people today would be “Yankee fans.” The factions encouraged this sort of loyalty by establishing what we might call “clubhouses” in Rome and later in other cities of the empire. In the later empire these groups even acquired some political influence (Junius Bassus, a consul of 331 CE, had himself portrayed driving a chariot in a mosaic; behind him are four horsemen wearing the colors of the four circus factions). In the first century CE, the Roman writer and statesman Pliny the Younger criticized this partisanship (Letters 9.6):

I am the more astonished that so many thousands of grown men should be possessed again and again with a childish passion to look at galloping horses, and men standing upright in their chariots. If, indeed, they were attracted by the swiftness of the horses or the skill of the men, one could account for this enthusiasm. But in fact it is a bit of cloth they favour, a bit of cloth that captivates them. And if during the running the racers were to exchange colours, their partisans would change sides, and instantly forsake the very drivers and horses whom they were just before recognizing from afar, and clamorously saluting by name. (translated by William Melmoth, H. A. Harris, Sport in Greece and Rome [Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1972], 220-21)

These stables competed for the services of the best charioteers, whose popular celebrity surpassed even that of modern sports heroes, and they were depicted in many statues and monuments, like the relief shown above from Neumagen, Germany (Trier Museum). One famous charioteer of the second century CE, Gaius Appuleius Diocles, left a detailed record of his career (CIL 6.10048). He began driving for the Whites at the age of 18; after 6 years, he switched to the Greens for 3 years, and then drove 15 years for the Reds before retiring at the age of 42. He won 1,462 of the 4,257 four-horse races in which he competed, and his winnings totaled nearly 36 million sesterces. Diocles’ career was unusually long; many charioteers died quite young (Fuscus at 24, Crescens at 22, Aurelius Mollicius at 20). Charioteers wore little body protection and only a light helmet; their practice of wrapping the reins tightly around their waists so they could use their body weight to control the horses was exceedingly dangerous in the case of accidents, since they could be dragged and trampled before they could cut themselves loose. Read the epitaph for the charioteer Scorpus written by the poet Martial.

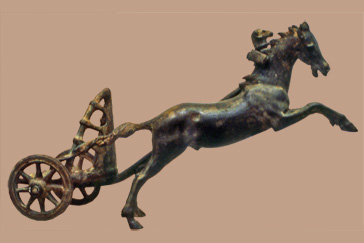

Chariots: Roman racing chariots were designed to be as small and lightweight as possible. Unlike military chariots, which were larger and often reinforced with metal, racing chariots were made of wood and afforded little support or protection for the charioteer, who basically had to balance himself on the axle as he drove, as can be seen in this statuette from Germany (Mainz Landesmuseum).

The bronze figurine from the British Museum shown here depicts a two-horse chariot (biga), though most races were run with four-horse chariots (quadrigae). Since horses were always harnessed abreast, more than four were uncommon, though we do hear of six- and even seven-horse teams (more information about racehorses).

Day at the Races: The ceremonies began with an elaborate procession (pompa) headed by the dignitary who was sponsoring the games, followed by the charioteers and teams, musicians and dancers, and priests carrying the statues of the gods and goddesses who were to watch the races; in this relief of the procession, the dieties are Jupiter, Castor, and Pollux. There were usually twelve races scheduled for a day, though this number was later doubled. The charioteers drew lots for their position in the starting gates; once the horses were ready, the white cloth (mappa) was dropped by the sponsor of the games; these two statues show an older magistrate and a younger one preparing to drop the cloth. At this signal, the gates were sprung, and up to twelve teams of horses thundered onto the track. The strategy was to avoid running too fast at the beginning of the race, since seven full laps had to be run, but to try to hold a position close to the barrier and round the turning posts as closely as possible without hitting them. As the race progressed, passions were intense both on and off the track; this painting by Alex Wagner gives some sense of the drama of these races, which is vividly recreated in the film Ben Hur. There were plenty of ways that teams from one stable could foul their opponents during a race, and sometimes even before it started (attempts to dope or poison horses and charioteers were not unknown). Fanatical partisans sometimes even resorted to magic, seeking to “hex” the rivals of their favorites. The following curse tablet represents an attempt to incapacitate the drivers of the Red faction:

Help me in the Circus on 8 November. Bind every limb, every sinew, the shoulders, the ankles and the elbows of Olympus, Olympianus, Scortius and Juvencus, the charioteers of the Red. Torment their minds, their intelligence and their senses so that they may not know what they are doing, and knock out their eyes so that they may not see where they are going—neither they nor the horses they are going to drive. (translated by H. A. Harris, Sport in Greece and Rome, 235-36)

Spectators could follow the progress of a race by watching the egg or dolphin counters, clearly shown in this relief of cupids racing. When the race was finally over, the presiding magistrate ceremoniously presented the victorious charioteer with a palm branch and a wreath while the crowds cheered wildly; the more substantial monetary awards for stable and driver would be presented later. This terracotta lamp shows a victorious charioteer processing in the Circus Maximus; he holds a palm branch and prize wreath, and one can see the spina behind him with the dolphins for counting laps, the obelisk, and a shrine to a deity. This mosaic commemorates a victorious team from the Reds, and this one, a victorious team from the Greens. The mosaic at right (from the Villa del Casale, Piazza Armerina, Sicily) shows the winning team processing toward the toga-clad magistrate to receive these tokens as a trumpeter signals the victory. The color of the charioteer's tunic indicates that he has driven for the Green faction, and the four reins are still wrapped around his waist.

Barbara F. McManus, The

College of New Rochelle

bmcmanus@cnr.edu

revised July,

2003