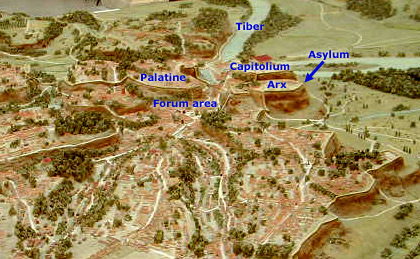

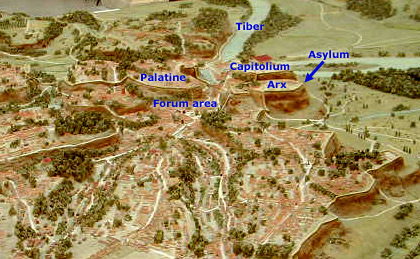

This model of Rome in the early Republican period gives a good sense of the geography of the area. At the bend of the Tiber are two facing hills, the Palatine and the Capitoline. The Capitoline itself has two summits, connected by a saddle or valley. The southwest summit closest to the Tiber was called the Capitolium (though this name was sometimes also applied to the hill as a whole), while the smaller but slightly higher northeast summit was called the Arx (“Citadel”). The grove-filled valley between them was a sacred area popularly known as the Asylum, because Rome's legendary founder Romulus was said to have designated this as a sanctuary for people from other areas seeking admission to the new city (see Livy Ab Urbe Condita 1.8.4-6).

The slopes of the Capitoline were fortified during a very early period of Rome's history, and the Capitolium was the site of a huge temple to Jupiter. The original temple was said to have been constructed by the last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, as a monument to his kingship, but he did not complete the temple before he was overthrown. So according to tradition the earliest temple was dedicated at the beginning of the Roman Republic. The chief deity of the temple was Jupiter Optimus Maximus (“best and the greatest”), also called Jupiter Capitolinus; both Juno and Minerva were also worshipped in this temple, so that these three deities came to be known as the Capitoline Triad. Because of its elevated position, the temple was frequently struck by lightning and had to be rebuilt many times. During the Republican period, the temple and its precinct (Area Capitolina, “Capitoline Square”) constituted the focal point of Rome's state religion. Each year the consuls began their terms of office by offering public sacrifices here, here Roman generals began military commands with solemn vows, and when they were successful, this is where their spectacular triumphal processions concluded. During the Empire, the Palatine Hill, home to the imperial palaces, began to rival the Capitoline as the seat of power, though emperors always carefully carried out traditional rituals at the Temple of Jupiter. Suetonius reports that Caligula built a bridge linking his palace on the Palatine with the Area Capitolina. Whether or not this was literally true (if so, the bridge didn't last), it is a symbolically apt indication of the shift in power and prominence between the two hills.

Poets often used the Capitolium as a kind of shorthand for the power, sovereignty, and immortality of Rome. Ovid, for example, wrote the following lines near the end of the Metamorphoses (15.826-828):

Romanique ducis coniunx Aegyptia taedae non bene fisa cadet, frustraque erit illa minata, servitura suo Capitolia nostra Canopo.

The Egyptian spouse of the Roman general, foolishly relying on the wedding torch, will fall, and her threats that our Capitoline will be enslaved to her Canopus will prove vain.

Canopus was a Egyptian coastal town located in the Nile Delta near Alexandria. In a striking image, Rome (the strongly masculine Capitoline hill) refuses to be subservient to Cleopatra's Egypt. (the distinctively feminine Nile Delta). When Horace wanted a powerful symbol to depict the immortality conveyed on him by his poetry, he used the rituals of civic power on the Capitolium as “more lasting than bronze or the lofty Pyramids” (Odes 3.30.6-9) :

Non omnis moriar multaque pars mei uitabit Libitinam; usque ego postera crescam laude recens, dum Capitolium scandet cum tacita uirgine pontifex.

I shall not wholly die -- a great part of me will escape the goddess of death. Fresh with the praise of posterity, I shall continue to grow as long as the Pontifex Maximus and the silent Vestal Virgin will climb the Capitoline Hill.Close this window when finished.