| ROMAN BATHS AND BATHING |

|

Of all the leisure activities, bathing was surely the most important for the greatest number of Romans, since it was part of the daily regimen for men of all classes, and many women as well. We think of bathing as a very private activity conducted in the home, but bathing in Rome was a communal activity, conducted for the most part in public facilities that in some ways resembled modern spas or health clubs (although they were far less expensive). A modern scholar, Fikret Yegül, sums up the significance of Roman baths in the following way (Baths and Bathing in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge: MIT, 1992):

The universal acceptance of bathing as a central event in daily life belongs to the Roman world and it is hardly an exaggeration to say that at the height of the empire, the baths embodied the ideal Roman way of urban life. Apart from their normal hygienic functions, they provided facilities for sports and recreation. Their public nature created the proper environment—much like a city club or community center—for social intercourse varying from neighborhood gossip to business discussions. There was even a cultural and intellectual side to the baths since the truly grand establishments, the thermae, incorporated libraries, lecture halls, colonnades, and promenades and assumed a character like the Greek gymnasium. (30)

Although wealthy Romans might set up a bath in their town houses or especially in their country villas, heating a series of rooms or even a separate building especially for this purpose, even they often frequented the numerous public bathhouses in the cities and towns throughout the empire. Small bathhouses, called balneae, might be privately owned, but they were public in the sense that they were open to the populace for a fee, which was usually quite reasonable. The large baths, called thermae, were owned by the state and often covered several city blocks. Fees for both types of baths were quite reasonable, within the budget of most free Roman males. Since the Roman workday began at sunrise, work was usually over at little after noon. About 2:00-3:00 pm, men would go to the baths and plan to stay for several hours of sport, bathing, and conversation, after which they would be ready for a relaxing dinner. Republican bathhouses often had separate bathing facilities for women and men, but by the empire the custom was to open the bathhouses to women during the early part of the day and reserve it for men from 2:00 pm until closing time (usually sundown, though we occasionally hear of a bath being used at night). For example, one contract for the management of a provincial bath specified that the facility would be open to women from daybreak until about noon, and to men from about 2:00 pm until sunset; although the women got the less desirable hours, their fee was twice as high as the men's, 1 as (a copper coin) for a woman and ½ as for a man. Mixed bathing was generally frowned upon, although the fact that various emperors repeatedly forbade it seems to indicate that the prohibitions did not always work. Certainly women who were concerned about their respectability did not frequent the baths when the men were there, but of course the baths were an excellent place for prostitutes to ply their trade.

Exercise: Bathing had a fairly regular ritual, and bathhouses were built to accommodate this. Upon entering the baths, individuals went first to the dressing room (apodyterium—this reconstruction drawing shows the men's dressing room in the Forum Baths in Pompeii), where there were niches and cabinets to store their street clothes and shoes (in the model above, the dressing room is on the left, farthest from the furnace; click here for a closer look). Many bathers were accompanied by one or more slaves to carry their gear and guard their clothes in the dressing rooms, but the bathhouses provided attendants who would watch over the belongings of the poorest for a fee. Sometimes the dressing room did double duty; for example, in the Stabian Baths in Pompeii the women's dressing room also served as a frigidarium, containing a small cold-water pool (note the graffito of a ship scratched into the post separating two niches in this room). Although the evidence is not clear about exactly what Romans wore when bathing, it seems probable that they did not exercise in the nude (as Greek males did) and may also have worn some light covering in the baths—perhaps the subligaculum. Within the baths special sandals with thick soles were needed to protect the feet from the heated floors.

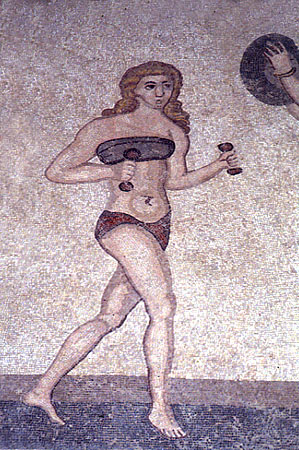

This drawing of the Stabian Baths shows the efficient design of a relatively small Republican bathhouse with separate facilities for men and women. The large central courtyard was the exercise ground (palaestra); it was surrounded by a shady portico which led into the bathing rooms. They might also take a swim in the large outdoor pool (natatio) such as this one in the Stabian Baths. After changing clothes and oiling their bodies, male bathers typically began their regimen with exercise, ranging from mild weight-lifting (as shown in the image at left), wrestling, various types of ball playing, running, and swimming (click here to find out more about Roman ball games). Although women athletes (like the one at left) are shown in the famous fourth-century CE mosaics from Piazza Armerina in Sicily, these apparently depict some sort of contest or competition rather than ordinary practice. Most of those exercising in the palaestrae were likely to be men.

Bathing: After exercise, bathers would have the dirt and oil scraped from their bodies with a curved metal implement called a strigil. Then the bathing proper began. Accompanied by a slave carrying their towels, oil flasks and strigils, bathers would progress at a leisurely pace through rooms of various temperature. They might start in the warm room (tepidarium), which had heated walls and floors but sometimes had no pool, and then proceed to the hot bath (caldarium), which was closest to the furnace. This room had a large tub or small pool with very hot water and a waist-high fountain (labrum) with cool water to splash on the face and neck. After this the bather might spend some time in the tepidarium again before finishing in the cold room (frigidarium) with a refreshing dip in the cold pool. Other rooms provided moist steam, dry heat like a sauna (laconicum), and massage with perfumed oils.

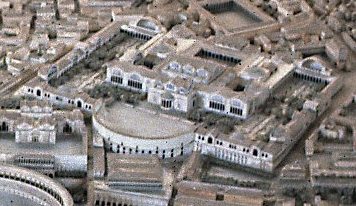

After their baths, patrons could stroll in the gardens, visit the library, watch performances of jugglers or acrobats, listen to a literary recital, or buy a snack from the many food vendors. Doubtless the baths were noisy, as the philosopher Seneca complained when he lived near a bathhouse in Rome, but the baths were probably very attractive places. Although most of the fine decor has not survived, many writers comment on the beauty and luxury of the bathhouses, with their well-lighted, airy rooms with high vaulted ceilings, lovely mosaics, paintings and colored marble panels, and silver faucets and fittings. This computer-generated reconstruction of the frigidarium of the baths of Hadrian at Lepcis Magna in Libya gives some idea of the splendor of the Roman thermae. The model at right depicts the baths of Trajan, located near the Colosseum. Enjoy a virtual bath by visiting these baths in Region III of VRoma, either via the web gateway or the anonymous browser.)

Heating System: Roman engineers devised an ingenious system of heating the baths—the hypocaust. The floor was raised off the ground by pillars and spaces were left inside the walls so that hot air from the furnace (praefurnium) could circulate through these open areas (see drawing of hypocaust design). Rooms requiring the most heat were placed closest to the furnace, whose heat could be increased by adding more wood. Click here to see the skeleton of a dog found in the hypocaust of a bath in Germany; it had apparently crawled beneath the floor seeking warmth and been asphyxiated by the fumes.

Latrines: Bathhouses also had large public latrines, often with marble seats over channels whose continuous flow of water constituted the first “flush toilets.” A shallow water channel in front of the seats was furnished with sponges attached to sticks for patrons to wipe themselves.

Barbara F. McManus, The

College of New Rochelle

bmcmanus@cnr.edu

revised June,

2011