| AUGUSTUS: A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS | |||

|

|

|

|

| Augustus as general | Augustus as statesman | Augustus as religious leader | Augustus as god |

| AUGUSTUS: A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS | |||

|

|

|

|

| Augustus as general | Augustus as statesman | Augustus as religious leader | Augustus as god |

Over time, Augustus dramatically altered the balance of power in the Roman system of government without seeming to do so; indeed, in Res Gestae 34.3 he explicitly claimed, “I exceeded all in influence [auctoritas], but I had no greater power than the others who were colleagues with me in each magistracy.” To characterize his power, he adopted the term princeps (“chief, leader”), which had long been applied to senators with the highest prestige and influence, but such circumlocutions only thinly masked the fact that Augustus, and Augustus alone, controlled all the most crucial areas of Roman government:

Augustus became a master of political propaganda, marshalling many different types of public display in order to make his new status and power seem appropriate and justified. For example, the statues at the top of this page suggest that it is fitting for one man, Augustus, to wield power in so many different spheres; see also this series of coins, or literary tributes such as these from the poets Horace and Vergil. Augustus even deployed his extensive public building program in such a way that it would support his position; for a few examples, see Augustus: Images of Power or visit the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine in Region X of VRoma or the Forum of Augustus in Region VIII; or visit both interactively by connecting as a guest via the web gateway.

|

Augustus included members of his extended family in this public display,

marking out a new status for the imperial household (domus principis or

domus Augusta) as identified with the state. He had begun this process

much earlier, during the Civil Wars, when he persuaded the Senate in 35 BCE to

set up public statues to his sister Octavia and his wife Livia and to grant

them sacrosanctity, a heretofore unprecedented extension of state protection to

women. He continued the policy by bestowing special honors, titles, and public

offices on his grandsons and heirs apparent (as in this coin depicting

Julia flanked by Gaius and

Lucius) even when they were still boys. This policy was apparently part of

his effort to secure the succession of imperial power for a family member

without appearing to create an imperial dynasty, but it was also a way to

emphasize the concept of family honor, with the imperial family the most

honorable of all. With such an emphasis on his own family, it is not surprising

that in his will Augustus adopted Livia into his lineage with the new name

Julia Augusta, giving her even closer ties to his family. Furthermore, members

of the imperial household, women as well as men, were involved in his building

program for the city of Rome, and their names, dedications, and even images

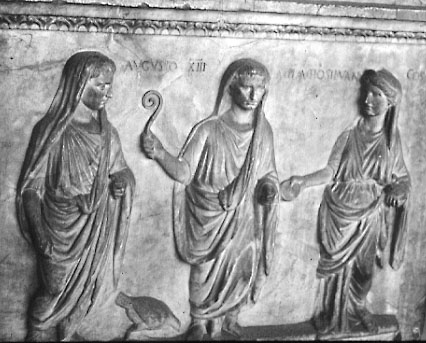

were to be found on public monuments throughout the city. The Altar of the

Lares above shows Augustus as augur, flanked by one of his grandsons and a

female member of his family (probably his wife Livia) with the attributes of a

priestess or goddess. One of the most striking monuments to combine state

functions with family imagery is the

Altar of Peace (Ara Pacis

Augustae), decreed by the Senate in 13 BCE to commemorate Augustus' safe

return from campaigns in Spain and Gaul and actually dedicated in 9 BCE on the

birthday of Livia, January 30. Both long sides of the altar depict a great

sacrificial procession designed to celebrate the peace and “restored

Republic” that Augustus brought to Rome. One side depicts a traditional

procession of senators, but

the

dominant side of the

procession is composed of members of the

family of Augustus, visually

presenting the sentiment expressed by the poet Ovid when writing about this

altar: “Pray that the household which is responsible for peace may,

together with that peace, last a long time” (“utque domus, quae

praestat eam, cum pace perennet,” Fasti 1.719).